|

Figure 1 : Congestion may change the direction of auto industry of China (from Want China Times). |

A more balance mobility’s footprint is a condition of a sustainable Asia Pacific increase

Mobility is composed of the

various services and means available for moving persons and goods. Rail, Road,

Air and Maritime are the four main mobility modes.

The dominant export-oriented development

model in the Asia-Pacific region over the past 15 years allowed considerable

growth while the movement of raw materials, sub-assemblies and finished

products were important issues of global competition.

This is also true with the

development now planned for the Asia Pacific region, where growth could become

more qualitative, less polluting, internally oriented with the aim of reducing

traffic congestion, improving short and medium distances transports.

As explained in our previous

post dated 31 Jan 2013, Asian Pacific countries were the fastest growing worldwide

areas during the past 15 years. Urbanization was both the condition and the

main result of this development. But Asian mega cities development is unprecedented in history

and presents a double-headed challenge:

global change -global risk.

Megacity's system could easily spin out of control with major

environmental problems such as power blackout, traffic congestion and air

pollution. Jakarta car congestion costs 5.4 bil $ annually while increasing

poor air quality. With business as usual conditions, pollution would increase

2-3 folds on 1990-2020 due to population growth, industrialization and

increased vehicle use.

Traffic congestion and

transport pollution have a huge cost in terms of health hazards, lost of hours

spent in transport congestion.

As we have explained in our last post outdoor particulate matter air

pollution in 2010 contributed to 1,270,000 premature deaths in Asia East (China

& North Korea), which is about 40% of the global worldwide total amounting

to 3,220,000 deaths. The burden of mobility is huge with the pollution of

motorcars and motorcycles in congested Chinese megacities

Cluster description of Asian Pacific countries

To study the 24 Asia-Pacific countries, we used-as in

our last post- a grouping in 5 clusters geographically, politically and

economically homogeneous (see Figure 2):

- Asia East (China, Korea Dem. Rep.);

- Asian Pacific high income (Brunei, Japan, Korea Rep., Singapore);

- Asia South (Bangladesh, Bhutan, India, Nepal, Pakistan);

- Asia Southeast (8 other ASEAN countries + Maldives, Sri Lanka, Timor-Leste);

- Australasia (Australia, New Zealand).

|

Figure 2 : The 5 clusters from the 24 Asian Pacific countries |

In each cluster various countries have similar GDP per

capita figures. The 5 cluster have altogether a 3,793 mil population - about

55% of the world population (6,896)- but with dissimilar land areas and

population outcomes by cluster (see Figures 3 to 6 below).

In the three most populous areas – Asia East, South and

Southeast- sustainability at stake is to continue rising income, while reducing

ecological footprint (CO2 emissions, water and air pollution), and improved

quality of life in large urban centers.

|

Figure 3 : Distribution of population (from World Bank Data) |

|

Figure 4 : Distribution of population density |

Each cluster has a major hub country such as China

(98% of Asia East population), Japan (69% of Asia Pacific High income), India

(78% of Asia South) or Australia (85% of Australasia).

But within the South East Asia, the situation is more

open: Indonesia is the largest country (39%), but Malaysia and Thailand have

the highest GDP per capita.

|

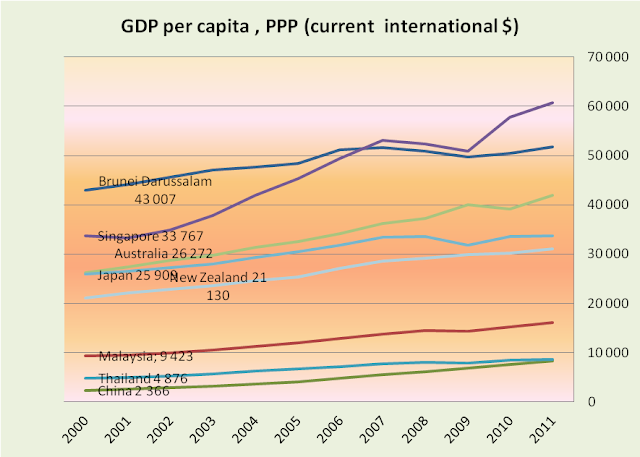

Figure 5 : Distribution of GDP per

capita, high income and high middle income countries (from World Bank Data)

|

|

Figure 6 : Distribution of GDP per capita, low midle income and low income countries (from World Bank Data) |

Passenger car ownership is a key factor

In many urban areas car private ownership is an

important status symbol. The relationship between household and car ownership

is mostly based on the income level.

We know that the relation between passenger car

ownership against per capita GDP is a S-shape growth curve (see “Vehicle ChinaPollution by 2050 Huo, Hong & alia”).

Initially car ownership growth are slow while costs

are high as compared to income, followed by a period of rapid uptake growth,

then later by a slowing of uptake as saturation levels are reached.

The

S-curve or Gompertz function is a

type of mathematical model used to describe the population in a confined space, as

birth rates first increase and then slow as resource limits are reached.

In the following Figures 7 & 8: the passenger car ownership per 1,000

people is plotted against per capita GDP in Asian Pacific countries (all data are

from the World Bank on 2000-2011).

|

Figure 7 : “S” shape growth curve relation of passenger car’s ownership against per Capita GDP growth (all figures from World Bank Data)

In Asia Pacific- if we except Singapore which is a

megacity country- growth patterns can be grouped into three categories:

|

- The North American type pattern – scarce population and huge distance- where saturation level is around 550 vehicles per 1,000 people when per capita GDP is higher than $20,000, is followed here by Australia and New Zealand.

- The European type pattern- denser population and compact urban development – where saturation level is around 450 vehicles per 1,000 people, is followed here by Japan, Brunei, Malaysia, Thailand and even China.

- The third pattern represented by Korea Rep, and some European countries, such as Denmark, and Ireland, show an even smaller rate of motor vehicle ownership, with a saturation level relatively lower—about 350 vehicles per 1,000 people. In these countries this low saturation level is caused partly by the high population density and the extensive public transportation system.

|

Figure 8 :Same “S” shape growth curve relation with a zooming on low and middle development countries (all figures from WorldBank Data) |

What might be the evolution of car ownership in the coming years?

The passenger cars’ ownership saturation level is a key factor

in estimating the total motor vehicle population growth. In particular, (see Figure 9) based on a continuation

of the GDP per capita growth such as during 1900-2011:

- China’s passenger car stock might increase seven-fold, to 380 mil

- Thailand might increase three-fold, Indonesia one 1/2- fold .

- Malaysia might increase one 1/2-fold and might be approaching the saturated level of 450 passenger car per 1,000 people .

Dargay and Gately assumed a saturation level of 850

(all vehicles) per 1,000 people and 620 cars per 1,000 people for the 26

countries (including China) that they studied .

However, Kobos et al. believe that it was impossible

for China—a highly populated country—to reach such a high saturation level.

Instead they propose a saturation level of 292 passenger vehicles per 1,000

people.

Button et al. set a range of 300 to 450 cars per 1,000

people for developing countries such as China.

We think as expressed by Kobos that the saturation

level of the third pattern (curve min) in the range of 290-300 passenger

vehicles should be more adapted. As done by Kobos & al. we need to examine the car ownership at the provincial level (see Figure 10).

Demand for vehicle trend to mirror the megacities

pattern concentration of wealth (see Figure 10), contrary to developed countries.

Increase in passenger vehicle will place serious strain

on land use, urban air pollution, and oil requirements.

|

Figure 10 : Passenger vehicle per

1,000 people by Chinese province, 2015 (from Kobos & al. 2003)

|

China and others Asian countries

rapidly evolving taste for automobile, all point towards a more integrated transport

policy where other factors such as access

to public transport, traffic limitations at peak hours, tax on fuel or vehicle to

compensate traffic congestion externalities might be discussed.

Innovative mobility- new type of car and rapid transit system -new investments, more stringent transport regulations and better law enforcement conditions are the conditions of a sustainable development. Poor policies in these areas may entail growing ecological footprint with health and environmental issues.

No comments:

Post a Comment